Alice Kilner | Group Sustainability Manager

Finding truly sustainable fuels to power the modern world is one of the key variables to achieving net zero. Out of all the fuel options present, hydrogen has become a buzzword in itself. The omnipresent element seems to be everywhere, yet nowhere, as limitations in handling and implementing the element as a fuel keep it from being a mainstream source of energy.

Our thought piece explores the uses of hydrogen, taking a non-biased approach to investigate if and how hydrogen as a fuel can be used in the built environment and the world.

Click any of the links below to quickly skip to that section:

- The basics of hydrogen

- Hydrogen in the automotive industry

- Hydrogen in buildings

- Current UK hydrogen plans

- Decarbonising buildings

The Basics of Hydrogen

Hydrogen is considered an alternative fuel to natural gas, spanning many potential purposes where it can be directly burnt or be utilised within a fuel cell. Unlike natural gas, hydrogen emits no carbon dioxide, only nitrogen oxide and water. Due to its similar properties, hydrogen is considered a cleaner fuel alternative, potentially serving as a direct replacement.

Definition: Fuel Cell

Hydrogen reacts with oxygen in the presence of a catalyst (often made from expensive platinum). This process strips out electrons that can then run through an electrical circuit, charging a battery that can power an electric motor.

In either case of use, hydrogen needs to be sourced. The element is dubbed ‘the most abundant in the universe’, however, it is often bonded with other elements, requiring electrolysis to split the elements and obtain pure hydrogen. The main methods of electrolysis are:

- Grey hydrogen – produced from burning fossil fuels. As of 2022, this equated to 90% of all hydrogen production.

- Blue hydrogen – the same process as grey, but any carbon dioxide emitted is removed and stored underground.

- Green hydrogen – produced using renewable energy. This is the most sustainable method of electrolysis.

- White hydrogen – recent observations claim natural reserves of hydrogen exist, providing a direct source. We cover more on the subject later.

EVs vs Hydrogen: The Automotive Battle

The most common areas of discourse for hydrogen as a green fuel is the automotive industry, where hydrogen and electric vehicles (EVs) are often pitted against each other.

The EV vs Hydrogen debate has existed for a while in the automotive industry.

If you were to compare the two, EVs are certainly ‘winning’ at the moment, or at least certainly from a consumer perspective. There are over 61,000 charging points in the UK compared to 15 hydrogen filling stations, with EVs also able to charge at owners’ homes. As of February 2024, there are over 1 million consumer EVs on the road, with growth expected around 20% year-on-year minimum. EVs on the road again tower over hydrogen figures, with just 300 hydrogen vehicles on the road in the UK – that includes public transport vehicles. There are questions about the range, charging times and embodied carbon of EVs, but it’s important to remember that we are still in the early development stages of electric vehicles. The technology will improve the more we learn – proven by the fact we can now recycle EV batteries.

It isn’t just a popularity contest, there are efficiency arguments that make it hard to justify hydrogen for consumer vehicles entirely. EVs are 77% efficient from ‘pump to wheel’, whilst hydrogen fuel cell vehicles are 33% efficient – still twice as efficient as combustion engines, though. In essence, it doesn’t make much sense to create extra steps in producing, storing and delivering hydrogen that turns into electricity, when you can use electricity in the first place with EV.

That being said, it isn’t a complete ‘no’ to hydrogen in vehicles. There could be scope within the commercial environment, specifically within the medium-range logistics route. EVs are a long way away from providing a solution that isn’t too heavy, whereas hydrogen can provide a long-range solution where you can refill at main strategic filling points such as ports. Hydrogen also can help clean city air, as seen with Transport for London’s fleet of hydrogen buses that operate around the city as we speak.

Hydrogen in Buildings

Within the built environment, the scope for hydrogen resides in replacing gas where possible. This affects boilers mostly, particularly within the residential market. Both domestic and commercial appliances are already tested for ignition performance with a 23% hydrogen blend. Some newer boilers come 100% hydrogen ready, and even older boilers can be converted to 100% ready with minimal changes. Performance-wise, hydrogen boilers are like-for-like with their gas counterparts, operating at around 70-80 degrees. Ground Source & Air Source Heat Pumps (GS/ASHPS) operate at a lower temperature, around 35-55 degrees. A hydrogen boiler may provide more heat, but in modern buildings and heating systems, the efficiency of said systems is far greater than older buildings & systems, meaning a higher temperature isn’t needed. This does not negate the need for hydrogen boilers though, as they are still a viable alterative to gas.

With the current gas infrastructure in the UK, the capacity for ~20% hydrogen blend with natural gas is possible with next to no changes. As CIBSE points out, due to hydrogens’ high energy density per unit mass, but a low volumetric energy density, a 20% blend only equates to around 7% decarbonisation. Although it does not eradicate the use of fossil fuels, it does pave the way to increasing hydrogen production.

It’s important to note that there are limitations to hydrogen. The greater flammability range poses a risk of ignition before the point of combustion. A faster flame speed means hydrogen is also prone to light-back (a combustion phenomenon that occurs when a flame enters a burner before it extinguishes). The property differences of the element bring to question claims that current gas infrastructure is capable of handling a 100% hydrogen conversion. Are current pipeline materials resistant to hydrogen embrittlement? If any seals and gaskets are rubber, these will need to be replaced with alternatives like Teflon. Are pipeline walls thick enough to stop the smaller hydrogen molecules from leaking? Pressure regulators and control systems need to be adapted or replaced to adhere to hydrogens’ different pressure and flow characteristics. The list goes on and on.

So, if the considerations required to convert natural gas infrastructure to 100% hydrogen are too lengthy and costly, could we simply switch everything to electric? You could, but it isn’t a feasible option. Current electricity capacity in the UK is around 100 GW. To cover the gas demand, an additional 50.74 GW of capacity would be required, bringing the total needed capacity to about 150.74 GW (this calculation assumes that the conversion efficiency of gas to electricity is around 50%, and the efficiency of renewable electricity sources is approximately 90%). Sourcing an electricity capacity expansion of 50% is a monumental task that requires all corners of renewables, nuclear and imported power to increase production – a task made even harder given the already challenging scope to phase out fossil fuels in the energy sector.

Where hydrogen could bring a wealth of benefits to the built environment is through combined heat and power fuel cells. Fuel cells produce electricity, but heat is also exerted by the cells. This heat can facilitate hot water and space heating, essentially acting as a heat recovery system. Government research claims this combined heat and power fuel cell for the built environment to be up to 90% efficient. A fuel cell can be placed directly in a building, or act as a sub-station to provide heat and power to a local network, essentially being self-sufficient if combined with an on-site electrolysis plant.

It’s estimated there are around 1.5 million commercial gas appliances in the UK, so generators, heating & cooling systems and catering equipment will all need either an alternative, clean fuel or a switch to electric.

A sustainable fuel, today

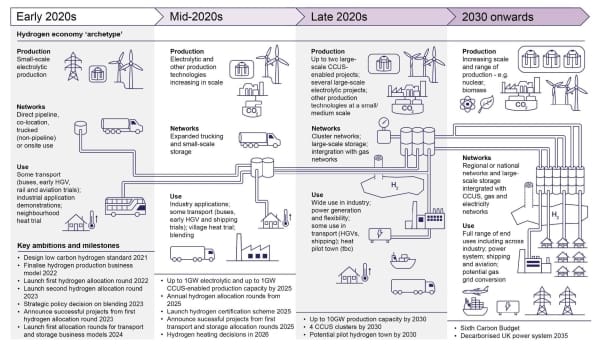

A lot of talk around hydrogen and a sustainable future is, admittedly, speculation, as we are constrained to worldwide government plans. So what is actually being done in the UK to enable hydrogen? The UK government have a hydrogen strategy in place, aiming to:

- Increase low carbon hydrogen production capacity to 10GW by 2030.

- Scale up production for low carbon hydrogen economy, supporting innovation and investment in the 2020s.

- Prioritise green and blue hydrogen production, to bring down the cost of sustainable fuel and grow the market.

Source: HYDROGEN STRATEGY DELIVERY UPDATE – Hydrogen Strategy Update to the Market: December 2023 (UK Government).

Positive strides have been made toward these goals, proven in the further £21m boost provided by the government towards seven hydrogen green fuel projects. From Suffolk to Shetland, the projects serve a range of purposes in producing green fuel for buses, trucks and trains, whilst also supporting local businesses in transitioning away from natural gas.

Some of the investment projects include:

- Suffolk Hydrogen run by Hydrab Power, which will make green hydrogen for low carbon service vehicles at the Sizewell C nuclear site.

- Tees Valley Hydrogen run by Exolum, which will build a new hydrogen refuelling station to help supply the local transport sector.

- Aberdeen Hydrogen Hub run by BP and Aberdeen City Council, which will provide cleaner fuel for the local fleet of electric buses.

The Aberdeen Hydrogen Hub. Source: BP.

The report claims that “by backing the UK hydrogen industry, we can support over 12,000 jobs and up to £11 billion in private investment by 2030” and that the funding of “The 7 projects have the potential to increase our capacity to make hydrogen by 800MW.”

Could there be more white hydrogen than first thought?

The government must continue to grow sustainable hydrogen production. As of 2022, 90% of the hydrogen produced worldwide is grey hydrogen. Green hydrogen is the ideal method present, but there is potentially another source to now consider – white hydrogen. Viritech, a hydrogen powertrain solution company, alongside other sources, have cited growing evidence that natural hydrogen sources are potentially as common as gas or oil. A village in Mali, Bourakebougou, has been using hydrogen to provide electricity since 2012 when a local burned himself by lighting a cigarette over what turned out to be a plume of white hydrogen. A mine in Albania was also discovered to release 200 tonnes a year of hydrogen at 84% purity. What was previously a hard element to detect – being colourless, odourless and rising in a very narrow vertical column – is now easier to find thanks to technological advances. A recent US Geological Survey report in The Financial Times believes as much as 5 trillion tonnes of white hydrogen may exist below the earth’s surface. For reference, one tonne of hydrogen produces the same amount of energy as three tones of petrol. That’s a lot of white hydrogen, if true!

One thing to note is the general grid decarbonisation targets set by the government. By 2035 the UK plans to have a fully decarbonised grid. This provides leniency with hydrogen production facilities, as ones that produce grey or blue hydrogen will eventually create green hydrogen if they source energy from the grid. Something to consider when looking at how the UK plans to expand hydrogen production.

Decarbonising Buildings

When examining sustainable solutions it is important to remember the sheer scale of the overall task to become net zero. The modern world stems from the industrial revolution, with whole processes, functions and infrastructures requiring adaptation or replacement. As a global community, we are still in the infant stages of finding answers. There won’t be an answer for every solution, and in many cases, there won’t be a single solution for a single issue. Adapting our world in the face of the climate crisis requires many solutions working together.

Hydrogen certainly has scope to form part of a larger solution. In the built environment, hydrogen can work alongside advances in ground and air source heat pumps, renewable energy, sustainable structural and fabric solutions, working towards tighter energy performance certification (EPC) requirements, and incorporating more stringent sustainability accreditations. What’s important is, as both an industry and global community, we share solutions to enable a better collective understanding.